It's hard to convince people these days that one lonely person can budge the vast stone wheel of apathy. The truth, though, is the same as it ever was: One pair of willing hands might inspire thousands or millions to push. That's the way the world is changed: hand by hand.

One person who found the courage to push the wheel is Ruth Coker Burks. Now a grandmother living a quiet life in Rogers, in the mid-1980s Burks took it as a calling to care for people with AIDS at the dawn of the epidemic, when survival from diagnosis to death was sometimes measured in weeks. For about a decade, between 1984 and the mid-1990s and before better HIV drugs and more enlightened medical care for AIDS patients effectively rendered her obsolete, Burks cared for hundreds of dying people, many of them gay men who had been abandoned by their families. She had no medical training, but she took them to their appointments, picked up their medications, helped them fill out forms for assistance, and talked them through their despair. Sometimes she paid for their cremations. She buried over three dozen of them with her own two hands, after their families refused to claim their bodies. For many of those people, she is now the only person who knows the location of their graves.

So much of the history of AIDS in America died with the people who lived it. What is left has often been shoved into the cabinet of Times Best Forgotten. Here, though, is a story from those days. It's a story about what courage can do.

The red door

It started in 1984, in a hospital hallway. Burks, now 55, was 25 and a young mother when she went to University Hospital in Little Rock to help care for a friend who had cancer. Her friend eventually went through five surgeries, Burks said, so she spent a lot of time that year parked in hospitals. That's where she was the day she noticed the door, one with "a big, red bag" over it. It was a patient's room. "I would watch the nurses draw straws to see who would go in and check on him. It'd be: 'Best two out of three,' and then they'd say, 'Can we draw again?' "

She knew what it probably was, even though it was early enough in the epidemic for the disease to be called GRID — gay-related immune deficiency — instead of AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome). She had a gay cousin in Hawaii and had asked him about the stories of a gay plague after seeing a report on the news. He'd told her, "That's just the leather guys in San Francisco. It's not us. Don't worry." Still, in her concern for him, she'd read everything she could find about the disease over the previous months, hoping he was right.

Whether because of curiosity or — as she believes today — some higher power moving her, Burks eventually disregarded the warnings on the red door and snuck into the room. In the bed was a skeletal young man, wasted to less than 100 pounds. He told her he wanted to see his mother before he died.

"I walked out and [the nurses] said, 'You didn't go in that room, did you?' " Burks recalled. "I said, 'Well, yeah. He wants his mother.' They laughed. They said, 'Honey, his mother's not coming. He's been here six weeks. Nobody's coming. Nobody's been here, and nobody's coming.' "

Unwilling to take no for an answer, Burks wrangled a number for the young man's mother out of one of the nurses, then called. She was only able to speak for a moment before the woman on the line hung up on her.

"I called her back," Burks said. "I said, 'If you hang up on me again, I will put your son's obituary in your hometown newspaper and I will list his cause of death.' Then I had her attention."

Her son was a sinner, the woman told Burks. She didn't know what was wrong with him and didn't care. She wouldn't come, as he was already dead to her as far as she was concerned. She said she wouldn't even claim his body when he died. It was a hymn Burks would hear again and again over the next decade: sure judgment and yawning hellfire, abandonment on a platter of scripture. Burks estimates she worked with more than a thousand people dying of AIDS over the course of the years. Of those, she said, only a handful of families didn't turn their backs on their loved ones. Whether that was because of religious conviction or fear of the virus, Burks still doesn't know.

Burks hung up the phone, trying to decide what she should tell the dying man. "I didn't know what to tell him other than, 'Your mom's not coming. She won't even answer the phone,' " she said. There was nothing to tell him but the truth.

"I went back in his room," she said, "and when I walked in, he said, 'Oh, momma. I knew you'd come,' and then he lifted his hand. And what was I going to do? What was I going to do? So I took his hand. I said, 'I'm here, honey. I'm here.' "

Burks said it was probably the first time he'd been touched by a person not wearing two pairs of gloves since he arrived at the hospital. She pulled a chair to his bedside, and talked to him, and held his hand. She bathed his face with a cloth, and told him she was there. "I stayed with him for 13 hours while he took his last breath on earth," she said.

She hasn't talked much about that day until recently. People always ask her why she wasn't afraid. "I have no idea," she said. "The thought of being afraid never occurred to me until after I was already deep into the AIDS crisis. I just asked God, 'If this is what you want me to do, just please don't let me or my daughter get it.' And He didn't."

'Someday, all of this is going to be yours'

Ruth Coker Burks' family came to Garland County in 1826. She was born in Hot Springs, and was a childhood friend of Bill Clinton's. While Clinton was in the White House, she said, they wrote back and forth, with Burks filling him in on all the hometown gossip from time to time.

Since at least the late 1880s, Burks' kin have been buried in Files Cemetery, a half-acre of red dirt on top of a hill above Central Avenue in Hot Springs. Drivers using Files Road as a cut-through to avoid the traffic on Central zip past the graveyard without even seeing it. If you stand in the right spot among the old, mossy tombstones in the winter, you can see a sliver of Lake Hamilton, glimmering like a cut sapphire through a gap in the trees.

When Burks was a girl, she said, her mother got in a final, epic row with Burks' uncle. To make sure he and his branch of the family tree would never lie in the same dirt as the rest of them, Burks said, her mother quietly bought every available grave space in the cemetery: 262 plots. They visited the cemetery most Sundays after church when she was young, Burks said, and her mother would often sarcastically remark on her holdings, looking out over the cemetery and telling her daughter: "Someday, all of this is going to be yours."

"I always wondered what I was going to do with a cemetery," she said. "Who knew there'd come a time when people didn't want to bury their children?"

Files Cemetery is where Burks buried the ashes of the man she'd seen die, after a second call to his mother confirmed she wanted nothing to do with him, even in death. "No one wanted him," she said, "and I told him in those long 13 hours that I would take him to my beautiful little cemetery, where my daddy and grandparents were buried, and they would watch out over him."

Burks had to contract with a funeral home in Pine Bluff for the cremation. It was the closest funeral home she could find that would even touch the body. She said she paid for the cremation out of her savings.

The ashes were returned to her in a cardboard box. She went to a friend at Dryden Pottery in Hot Springs, who gave her a chipped cookie jar for an urn. Then she went to Files Cemetery and used a pair of posthole diggers to excavate a hole in the middle of her father's grave.

"I knew that Daddy would love that about me," she said, "and I knew that I would be able to find him if I ever needed to find him." She put the urn in the hole and covered it over. She prayed over the grave, and it was done.

Over the next few years, as she became one of the go-to people in the state when it came to caring for those dying with AIDS, Burks would bury over 40 people in chipped cookie jars in Files Cemetery. Most of them were gay men whose families would not even claim their ashes.

"My daughter would go with me," Burks said. "She had a little spade, and I had posthole diggers. I'd dig the hole, and she would help me. I'd bury them and we'd have a do-it-yourself funeral. I couldn't get a priest or a preacher. No one would even say anything over their graves."

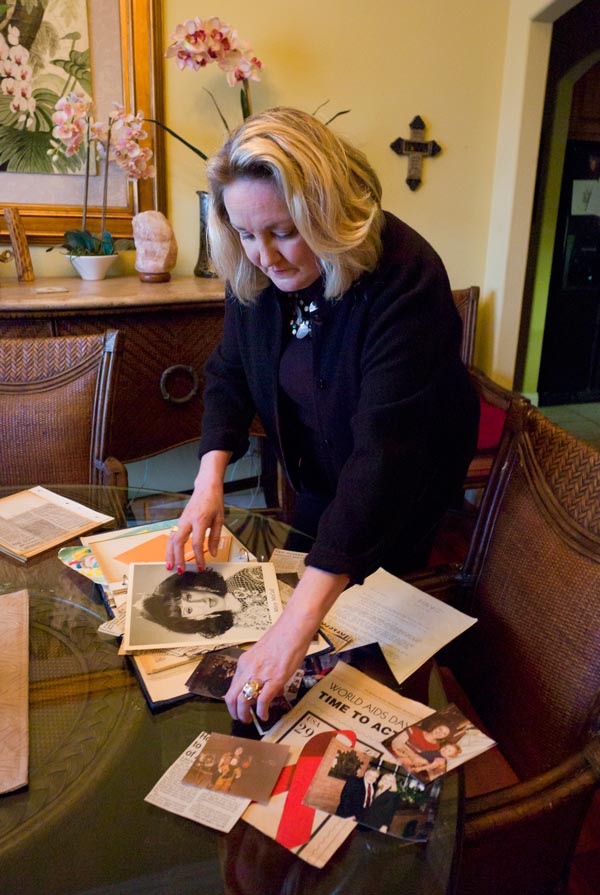

She believes the number was 43, but she isn't sure. Somewhere in her attic, in a box, among the dozens of yellowed day planners she calls her Books of the Dead, filled with the appointments, setbacks and medications of people 30 years gone, there is a list of names.

Burks said she always made a last effort to reach out to families before she put the urns in the ground. "I tried every time," she said. "They hung up on me. They cussed me out. They prayed like I was a demon on the phone and they had to get me off — prayed while they were on the phone. Just crazy. Just ridiculous."

She learned to say the funerals herself, after being rebuffed by preachers and priests too many times. Even so, she said she never doubted what she was doing. "It never made me question my faith at all," she said. "I knew that what I was doing was right, and I knew that I was doing what God asked me. It wasn't a voice from the sky. I knew deep in my soul."

Elephant

After she cared for the dying man at University Hospital, people started calling, asking for her help. "They just started coming," she said. "Word got out that there was this kind of wacko woman in Hot Springs who wasn't afraid. They would tell them, 'Just go to her. Don't come to me. Here's the name and number. Go.'... I was their hospice. Their gay friends were their hospice. Their companions were their hospice."

Before long, she was getting referrals from rural hospitals all over the state. Financing her work through donations and sometimes her own pocket, she'd take patients to their appointments, help them get assistance when they could no longer work, help them get their medicines, and try to cheer them up when the depression was dark as a pit. She said many pharmacies wouldn't handle prescriptions for AIDS drugs like AZT, and there was fear among even those who would. Somewhere, she said, she has a large coffee can full of 30 year-old pens. Once pharmacy clerks learned she was working with AIDS patients, she said, many of them would insist she keep the pen after signing a check. "They didn't want it in their building," she said. "They would come out with a can of Lysol and spray me out the door."

She'd soon stockpiled what she called an "underground pharmacy" in her house. "I didn't have any narcotics, but I had AZT, I had antibiotics," she said. "People would die and leave me all of their medicines. I kept it because somebody else might not have any."

Burks said the financial help they gave patients — from burial expenses to medications to rent for those unable to work — couldn't have happened without the support of the gay clubs around the state, particularly Little Rock's Discovery. "They would twirl up a drag show on Saturday night and here'd come the money," she said. "That's how we'd buy medicine, that's how we'd pay rent. If it hadn't been for the drag queens, I don't know what we would have done."

Norman Jones is the owner of Discovery. Opened in 1979, the club once served a primarily gay clientele, though now the crowd is often mixed. He's old enough to remember the fear of the early days of the epidemic. In 1988, Jones helped found the charity group Helping People with AIDS, with which Burks worked. The group is still around, helping those with the disease. "She worked with us for several years there," Jones said. "She went out and did home visits, and she'd work determining who would qualify for the money."

Jones said that as AIDS moved into Arkansas, he and the club's employees decided to do something to help. "The impersonators and the bartenders that worked at the club and I decided that we'd start doing once-a-year benefits to start a fund called Helping People with AIDS," he said. "We started raising money every year and we still do so today, over 25 years later." Jones said the money generated by the fund, as well as a percentage of the club's sales, have helped the AIDS Foundation and other groups assisting those with the disease.

After AIDS came to Arkansas, Jones said, he started to see the changes almost immediately. Even a rumor that someone had HIV could make their friends shun them. "We had so many people who were affected by it when it first hit that it was like, wham!" he said. "It was like you were being thrown up against a brick wall. Everyone said, 'Don't touch them. Don't talk to them.' " Even something as slight as losing a few pounds was enough to make people afraid to associate with a person, Jones said. The fear was rampant. "It made everyone feel aware that something was happening out there," he said. "We didn't know what was happening, but there was a fear of it."

Burks' stories from that time border on nightmarish, with her watching one person after another waste away before her eyes. She would sometimes go to three funerals a day in the early years, including the funerals of many people she'd befriended while fighting the disease. Many of her memories seem to have blurred together into a kind of terrible shade. Others are told with perfect, minute clarity.

There was the man whose family insisted he be baptized in a creek in October, three days before he died, to wash away the sin of being gay; whose mother pressed a spoonful of oatmeal to his lips pleading, "Roger, eat. Please eat, Roger. Please, please, please" until Burks gently took the spoon and bowl from her; who died at 6-foot-6 and 75 pounds; whose aunts came to his parents' house after the funeral in plastic suits and yellow gloves to double-bag his clothes and scrub everything, even the ceiling fan, with bleach.

She recalled the odd sensation of sitting with dying people while they filled out their own death certificate, because Burks knew she wouldn't be able to call on their families for the required information. "We'd sit and fill it out together," she said. "Can you imagine filling out your death certificate before you die? But I didn't have that information. I wouldn't have their mother's maiden name or this, that or the other. So I'd get a pizza and we'd have pizza and fill out the death certificate."

She remembered the Little Rock man who "had so much fluid on his lungs that he couldn't breathe. He couldn't talk, and he would gag when he was trying to talk. His mother, we had called and called and called. ... He wanted to talk to his mother and wanted me to try again. I got the answering machine, and I just handed the phone to him. He cried and gagged. It was excruciating listening to him ask his mother if she'd come to the hospital. She never came. The day before the funeral, she called and asked if she could come to the funeral. He's buried in [Files] cemetery."

She recalled the mother who called Burks up and demanded to know how much longer it would be before her son died. " 'I just want to know, when is he going to die?' " Burks recalled the woman asking. "'We have to get on with our lives, and he's holding up our lives. We can't go on with our lives until he dies. He's ruined our lives, and we don't want people up here to know [he has AIDS], so how long do you think he's going to stay here?' Like it was a punishment to her."

Billy, however, is the one who hit her hardest, and the one she remembers most clearly of all. He was one of the youngest she ever cared for, a female impersonator in his early 20s. He was beautiful, she said, perfect and fine-boned. She still has one of Billy's dresses in her closet up in Rogers: a tiny, flame-red designer number, intricate as an orchid. It was Billy's mother, she said, who called up to ask how much longer it would be before they could get on with their lives.

As Billy's health declined, Burks accompanied him to the mall in Little Rock to quit his job at a store there. Afterward, she said, he wept, Burks holding the frail young man as shoppers streamed around them. "He broke down just sobbing in the middle of the mall," she said. "I just stood there and held him until he quit sobbing. People were looking and pointing and all that, but I couldn't care less."

Once, a few weeks before Billy died — he weighed only 55 pounds, the lightest she ever saw, light as a feather, so light that she was able to lift his body from the bed with just her forearms — Burks had taken Billy to an appointment in Little Rock. Afterward, they were driving around aimlessly, trying to get his spirits up. She often felt like crying in those days, she said, but she couldn't let herself. She had to be strong for them.

"He was so depressed. It was horrible," she said. "We were driving by the zoo, and somebody was riding an elephant. He goes: 'You know, I've never ridden an elephant.' I said: 'Well, we'll fix that.' " And she turned the car around. Somewhere, in the boxes that hold all her terrible memories, there's a picture of the two of them up on the back of the elephant, Ruth Coker Burks in her heels and dress, Billy with a rare smile.

Two or more

When it was too much, she said, she'd go fishing. And it wasn't all terrible. While Burks got to see the worst of people, she said, she was also privileged to see people at their best, caring for their partners and friends with selflessness, dignity and grace. She said that's why she's been so happy to see gay marriage legalized all over the country.

"I watched these men take care of their companions, and watch them die," she said. "I've seen them go in and hold them up in the shower. They would hold them while I washed them. They would carry them back to the bed. We would dry them off and put lotion on them. They did that until the very end, knowing that they were going to be that person before long. Now, you tell me that's not love and devotion? I don't know a lot of straight people that would do that."

Sometimes, she would listen to the confessions of the dying. "Whatever they wanted to tell their God, I would help them tell their God," she said. "I figured, if the religious people weren't going to do it, someone has to. If God wanted me to do this, then surely I can say: Yes, you're going to heaven. ... The Bible says that if you're two or more, and you ask God for forgiveness, He will forgive you. There were two of us, so that was the best I could do."

In all the years she worked with AIDS patients, she said, she never wore gloves unless the patients had broken skin. It was touching them, she believes, that kept those she cared for alive longer than others. By the 1990s, experts in the field were beginning to take note.

"My [HIV] patients lived two years longer than the national average," Burks said. "They would send people from all over the world to the National Institutes of Health, they would send them to the CDC, and they would send them to me. They sent them to me so they could see what I was doing that helped them live. I think it was because I loved them. They were like my children, even though I was burying people my age."

Burks helped care for Raymond Harwood, a Hot Springs resident who died in 1994 at age 42. His father, Jim Harwood, said Burks met Raymond through an outreach program sponsored by the local Catholic Church. Jim recalled Burks as a very caring person. "She was absolutely sweet," Harwood said. "One of the kindest, sweetest people I've ever known."

God, Harwood said, has a hand in everything, so He had a hand in bringing Burks into their lives. Harwood said he was surprised to hear from Burks that some parents abandoned their children when they were diagnosed with AIDS.

"I wasn't brought up that way," Harwood said. "Are you going to desert your son? I don't care what he did. He could have gone out and murdered people. He's still your son. You may not like what he does, but you love him."

Back to God

Ruth Coker Burks had a stroke five years ago, early enough in her life that she can't help but believe that the stress of the bad old days had something to do with it. After the stroke, she had to relearn everything: to talk, to feed herself, to read and write. It's probably a miracle she's not buried in Files Cemetery herself.

After better drugs, education, understanding and treatment made her work obsolete, she moved to Florida for several years, where she worked as a funeral director and a fishing guide. When Bill Clinton was elected president, she served as a White House consultant on AIDS education.

A few years ago, she moved to Rogers to be closer to her grandchildren. In 2013, she went to bat for three foster children who were removed from the elementary school at nearby Pea Ridge after administrators heard that one of them might be HIV positive. Burks said she couldn't believe she was still dealing with the same, knee-jerk fears in the 21st century.

The work she and others did in the 1980s and 1990s has mostly been forgotten, partly because so many of those she knew back then have died. She's not the only one who did that work, but she's one of the few who survived. And so she has become the keeper of memory.

She was surprised in recent months when a producer with the oral history project StoryCorps reached out to her, asking her to tell her story on tape. Part of that interview was eventually broadcast on National Public Radio. She talked to the BBC this week, and other requests for interviews keep coming. She honestly seems a little shocked that anyone cares after all these years.

She talks of those days like an old soldier, tears only touching her eyes when she speaks of Billy, or her father's grave, or how she sometimes wonders if her choice to help AIDS patients as a young woman, and the ostracism that brought, may have kept her from being everything she could have been. Still, she clearly sees those years as the time when she had a mission, maybe even one ordained by a higher power. Too, she said, she loved and believes she was loved by the people whose lives she touched — every one. Even as they were dying, they showed her what bravery is, and brought joy into her life. "They were good days," she said, "because I was blessed with handing these people back to God."

She hasn't been back to Files Cemetery since her stroke. While she made sure it was kept up back when she lived in Hot Springs, it appeared to have been let go a bit when the reporter visited in late December, some of the tombstones pushed over and broken, the snag of a dead oak left to rot among the graves. Even without knowing the story of the place, it might have been downright spooky if not for the constant stream of traffic cruising by at 10 miles an hour over the speed limit.

Before she's gone, she said, she'd like to see a memorial erected in the cemetery. Something to tell people the story. A plaque. A stone. A listing of the names of the unremembered dead that lie there.

"Someday," she said, "I'd love to get a monument that says: This is what happened. In 1984, it started. They just kept coming and coming. And they knew they would be remembered, loved and taken care of, and that someone would say a kind word over them when they died."