Octavia Butler

Octavia Estelle Butler (June 22, 1947 – February 24, 2006) was an American science fiction writer. A multiple recipient of both the Hugo and Nebula awards, Butler was one of the best-known women in the field. In 1995, she became the first science fiction writer to receive the MacArthur Fellowship, nicknamed the "Genius Grant".

Rise To Success

Even though Butler's mother wanted her to become a secretary with a steady income, Butler continued to work at a series of temporary jobs, preferring the kind of mindless work that would allow her to get up at two or three in the morning to write. Success continued to elude her, as an absence of useful criticism led her to style her stories after the white-and-male-dominated science fiction she had grown up reading. She enrolled at California State University, Los Angeles, but then switched to taking writing courses through UCLA Extension.

Butler finally caught her break during the Open Door Workshop of the Screenwriters' Guild of America, West, a program designed to mentor minority writers. Her writing impressed one of the Writers Guild teachers, noted science-fiction writer Harlan Ellison, who encouraged her to attend the six-week Clarion Science Fiction Writers Workshop in Clarion, Pennsylvania. There, Butler met the writer and later longtime friend Samuel R. Delany. She also sold her two first stories: "Child Finder" to Ellison, for his anthology The Last Dangerous Visions (controversially, still unpublished), and "Crossover" to Robin Scott Wilson, the director of Clarion, who published it as part of the 1971 Clarion anthology.

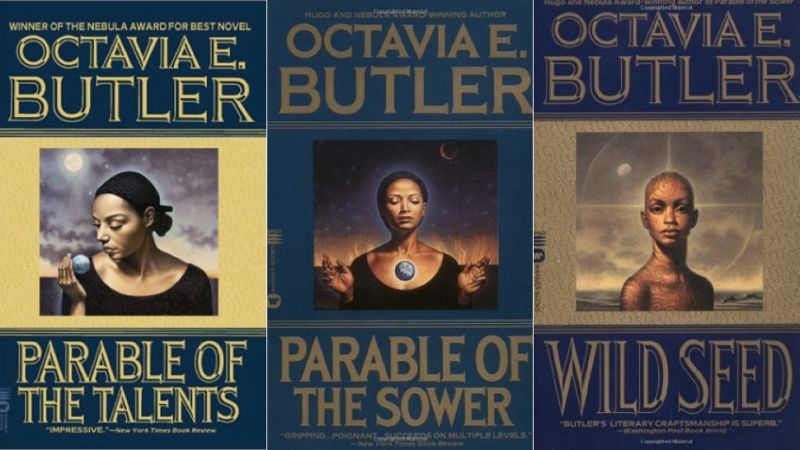

For the next five years, Butler worked on the series of novels that would later become known as the Patternist series: Patternmaster (1976), Mind of My Mind (1977), and Survivor (1978). In 1978, she was finally able to stop working at temporary jobs and live on her writing. She took a break from the Patternist series to research and write Kindred (1979), but went back to finish it by writing Wild Seed (1980) and Clay's Ark (1984).

Butler's rise to prominence began in 1984 when "Speech Sounds" won the Hugo Award for Short Story and, a year later, Bloodchild won the Hugo Award, the Locus Award, and the Science Fiction Chronicle Reader Award for Best Novelette. In the meantime, Butler traveled to the Amazon rainforest and the Andes to do research for what would become the Xenogenesis trilogy: Dawn (1987), Adulthood Rites (1988), and Imago (1989). These stories were republished in 2000 as the collection Lilith's Brood.

During the 1990s, Butler worked on the novels that solidified her fame as a writer: Parable of the Sower (1993) and Parable of the Talents (1998). In 1995, she became the first science-fiction writer to be awarded a John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation fellowship, an award that came with a prize of $295,000.

"Who am I? I am a forty-seven-year-old writer who can remember being a ten-year-old writer and who expects someday to be an eighty-year-old writer. I am also comfortably asocial—a hermit.... A pessimist if I'm not careful, a feminist, a Black, a former Baptist, an oil-and-water combination of ambition, laziness, insecurity, certainty, and drive."

Octavia E. Butler, reading the self-penned description of herself included in Parable of the Sower during a 1994 interview with Jelani Cobb. In 1999, after her mother's death, Butler moved to Lake Forest Park, Washington. The Parable of the Talents had won the Science Fiction Writers of America's Nebula Award for Best Science Novel and she had plans for four more Parable novels: Parable of the Trickster, Parable of the Teacher, Parable of Chaos, and Parable of Clay. However, after several failed attempts to begin The Parable of the Trickster, she decided to stop work in the series. In later interviews, Butler explained that the research and writing of the Parable novels had overwhelmed and depressed her, so she had shifted to composing something "lightweight" and "fun" instead. This became her last book, the science-fiction vampire novel Fledgling (2005).

Influence

In interviews with Charles Rowell and Randall Kenan, Butler credited the struggles of her working-class mother as an important influence on her writing. Because Butler's mother received little formal education herself, she made sure that young Butler was given the opportunity to learn by bringing her reading materials that her white employers threw away, from magazines to advanced books. She also encouraged Butler to write. She bought her daughter her first typewriter when she was ten years old, and, seeing her hard at work on a story, casually remarked that maybe one day she could become a writer, causing Butler to realize that it was possible to make a living as an author. A decade later, Mrs. Butler would pay more than a month's rent to have an agent review her daughter's work. She also provided Butler with the money she had been saving for dental work to pay for Butler's scholarship so she could attend the Clarion Science Fiction Writers Workshop, where Butler sold her first two stories.

A second person to play an influential role in Butler's work was American writer Harlan Ellison. As a teacher at the Open Door Workshop of the Screen Writers Guild of America, he gave Butler her first honest and constructive criticism on her writing after years of lukewarm responses from composition teachers and baffling rejections from publishers. Impressed by her work, Ellison suggested she attend the Clarion Science Fiction Writers Workshop, and even contributed $100 towards her application fee. As the years passed, Ellison's mentorship became a close friendship.

Point of view

Butler began reading science fiction at a young age, but quickly became disenchanted by the genre's unimaginative portrayal of ethnicity and class as well as by its lack of noteworthy female protagonists. She then set to correct those gaps by, as De Witt Douglas Kilgore and Ranu Samantrai point out, "choosing to write self-consciously as an African-American woman marked by a particular history" — what Butler termed as "writing myself in". Butler's stories, therefore, are usually written from the perspective of a marginalized black woman whose difference from the dominant agents increases her potential for reconfiguring the future of her society.

Audience

Publishers and critics have tended to label Butler's work as science fiction, but while Butler enjoyed working in what she called "potentially the freest genre in existence", she resisted being branded a genre writer. As many critics have pointed out, her narratives have drawn attention of people from varied ethnic and cultural backgrounds, and she herself claimed to have three loyal audiences: black readers, science-fiction fans, and feminists.

Interviews

Charlie Rose interviewed Octavia Butler in 2000 soon after the award of a MacArthur Fellowship. The highlights are probing questions that arise out of Butler's personal life narrative and her interest in becoming not only a writer, but a writer of science fiction. Rose asked, "What then is central to what you want to say about race?" Butler's response was, "Do I want to say something central about race? Aside from, 'Hey we're here!'?" This points to an essential claim for Butler that the world of science fiction is a world of possibilities, and although race is an innate element, it is embedded in the narrative, not forced upon it.

In an interview by Randall Kenan, Octavia E. Butler discusses how her life experiences as a child shaped most of her thinking. As a writer, Butler was able to use her writing as a vehicle to critique history under the lenses of feminism. In the interview, she discusses the research that had to be done in order to write her bestselling novel, Kindred. Most of it is based on visiting libraries as well as historic landmarks with respect to what she is investigating. Butler admits that she writes science fiction because she does not want her work to be labeled or used as a marketing tool. She wants the readers to be genuinely interested in her work and the story she provides, but at the same time she fears that people will not read her work because of the "science fiction" label that they have.

More at Wikipedia.